Civil War Letters: Identifying and Researching Authors

In the 160 years since the end of the Civil War, many letters written during that time have lost valuable historical context as they were passed down through generations, sold and resold, and finally made their way into the hands of people that want to know more about them. Sometimes identifying the authors and regiments of Civil War letters can be as simple as reading the signature at the end of a letter, other times it takes more detective work.

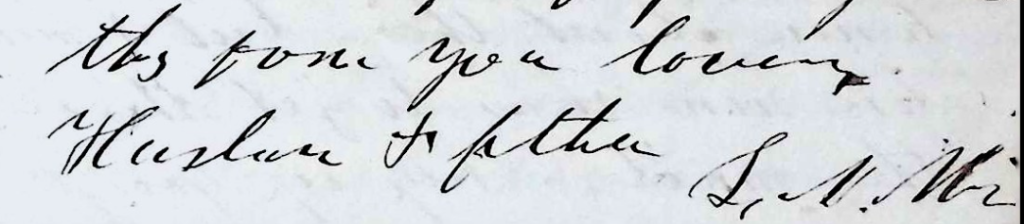

To illustrate some of the ways a letter can be narrowed down or identified through research, we’re going to look at a letter that recently became part of the Research Arsenal collection through a group of unidentified Civil War era letters by various authors. The letter is signed with the initials “L. N. M.” but contains no dateline, location or regiment.

While knowing all three initials of the author is helpful, it’s too broad to lead us to a regiment all on its own. We also don’t know the exact date the letter was written or from where, so the next thing we have to do is look at the content of the letter itself and hope that we can find more clues.

Looking for Clues in the Content of Civil War Letters

In the beginning of the letter, L. N. M. writes (all quotes adjusted for spelling and punctuation), “the morning I had to get up and go to the sutler to take Everett’s place as he is not very well” and that “Two of the Lebanon Boys and Everett and I have fixed us up a board tent or shanty where we can be by ourselves.” Everett, then, is clearly someone close to the author and his wife, raising the possibility that it could be a brother or son, though it is just as likely to be a close personal friend. The “Lebanon Boys” also suggests that the author is from somewhere in Pennsylvania or New Hampshire, rather than further west.

Further in the letter, we get a series of information that greatly narrows down the possibilities:

“I expect the sutler will [want] all the time I can spare as he has had a place up with his clerk so I shall have as good a chance as I had to Fort Jefferson. I have thought pretty strong of sending Everett home with Mr. Williams, but he can do as he is a mind to. His shirts are getting rather thin I am going to take one to mend the other I have to economize on his clothes.”

From the above excerpt, it’s clear that Everett is likely the son of the author, and probably very young as L. N. M. is able to send him home, meaning he isn’t a regularly enlisted soldier. L. N. M. also reveals that the regiment was once stationed at Fort Jefferson, Florida, which means we now have a location to research for more clues.

Fort Jefferson is one of the United States’ largest forts and located in the Dry Tortugas area of Florida. It was constructed in the 1840s and occupied by Union forces throughout the Civil War. A quick scan of the Wikipedia page for Fort Jefferson reveals that the following regiments were stationed there during the Civil War: 2nd US Artillery, 6th New York Zouaves, 7th New Hampshire Infantry, 90th New York Infantry, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry, and the 110th New York Infantry. There is an excellent chance that L. N. M. belonged to one of these six regiments. In addition, the 110th New York Infantry can probably be discounted as it served at Fort Jefferson through the end of the war, while L. N. M.’s regiment has clearly already moved on from that post.

Finally, L. N. M. writes that “Cap House thinks the select men will have to come over. He gets his information from Sham by the way of his wife. He is in the legislature you know.” Knowing that there is a captain named House in L. N. M.’s regiment is a tremendous clue. Using the National Park Services Soldiers and Sailors Database we can search for a “Captain House” in the six regiments we identified as having been stationed at Fort Jefferson. Of the sixth regiments, only one had a captain with the last name House: Captain Jerome B. House of the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers.

Using Regimental Rosters to Identify Authors of Civil War Letters

Now that we’ve narrowed down L. N. M.’s regiment, the next step is to see if we can identify him and figure out his full name. The best place to start would be with a roster of the men serving in Company C of the 7th New Hampshire Infantry, which is the company that was commanded by Jerome B. House. The Internet Archive has the “Report of the Adjutant-General of the State of New Hampshire” which contains a complete roster of the 7th New Hampshire Infantry. Reading through the names, the only person with the initials “L. N. M.” is a musician named “Leonard N. Miner” who enlisted December 3, 1861 and mustered out in December 1864.

While it is very likely that Leonard N. Miner is the author of the letter, to make absolutely sure the next step is to research his family to see if the other information from the letter fits well with it. Census records along with genealogy websites like ancestry.com and familysearch.org are an excellent resource for looking up individuals once you learn their name. In this case, Leonard Miner’s gravestone is available on findagrave.com and tells us that he had a son named Everett, which is very strong confirmation that this is the correct person.

Finally, now that we’ve identified the regiment and the author of the letter, it is possible to narrow down the time it was written. The 7th New Hampshire Infantry was stationed at Fort Jefferson, Florida from March until June 1862, so the letter was likely written sometime after that. Captain Jerome B. House was severely wounded at Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863 and died of his wounds in Lebanon, New Hampshire on October 7, 1863, so the letter can be assumed to have been written before July, 1863. Throughout that time, the 7th New Hampshire Infantry served in the Department of the South.

With today’s online resources, it is much easier to research and restore valuable context to Civil War letters that may have been lost over the years. Everything mentioned in a letter is a potential clue to finding its author, and location information can be especially useful for narrowing down the regiment in which the author served. Even if you can’t identify the exact individual, knowing their regiment, or Corps, helps to add important historical background to the letter, and might help future researchers and historians narrow things down further.

In the meantime, if you’re lucky enough to own a piece of Civil War history, be sure to keep all the information you know about the item with it, so that it can be preserved for future generations.

To see thousands of Civil War Letters like the one discussed above, sign up for membership at the Research Arsenal here.