Research Arsenal Spotlight 1: Chester Chapman Letters

This week were spotlighting a collection of over 70 letters on the Research Arsenal, made possible through a partnership with Spared & Shared. These letters were written by Chester Chapman of Montville, New London, Connecticut during his service from 1861 to 1865.

Chester Chapman’s Service in the 4th Connecticut Infantry and Reorganization into the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery

Chapman enlisted in the 4th Connecticut Infantry on May 22, 1861 and was assigned to company D. In an early letter written on August 29, 1861, Chester Chapman wrote to his wife, Martha Loretta (Williams) Chapman about the conditions of the food in his camp at Frederick, Maryland.

“I am writing everything that I can think of. The boys are eating supper and they want me to let you know what they have got for supper. They have got boiled rice, which is little less than half done, and boiled water seasoned with oak leaves for tea, sweetened with molasses. I had rather eat it than drink it. So I am a going to wait until they stop eating, then I am a going to eat some of the molasses on a piece of bread. We have just half enough to eat and very bad treatment. Do not let anyone see this for if they should find out what I have been writing, they would take me up as a secessionist and God knows I hate the sound of the name.”

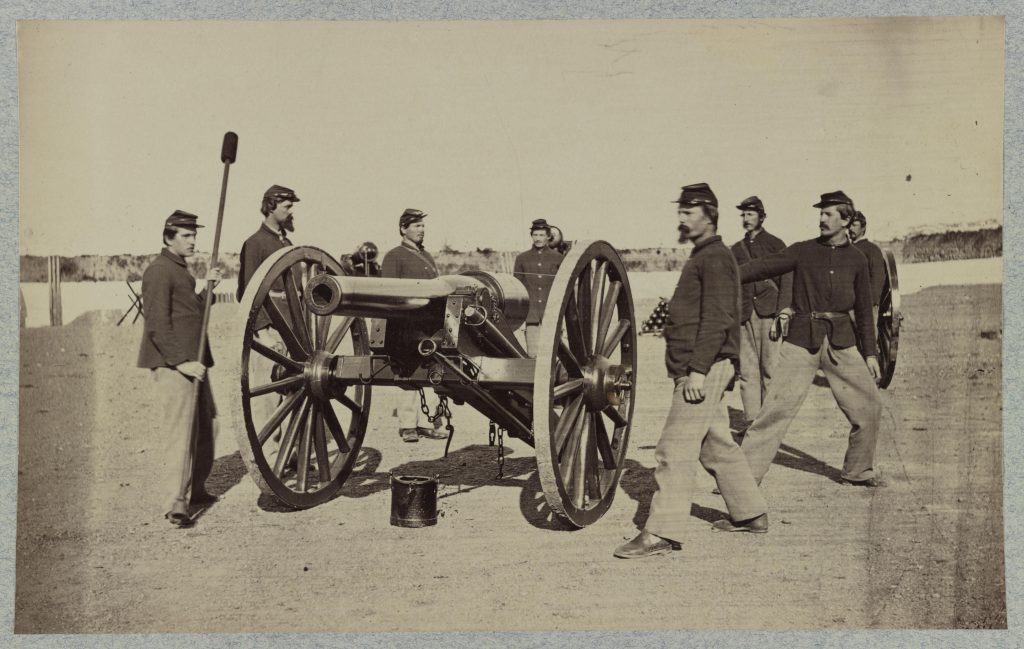

In September, 1861, Chapman received word that his regiment would be converted to artillery and the unit was soon after designated as the 1st Connecticut Heavy Artillery, under the command of a new Colonel, Robert Ogden Taylor. Chapman wrote to Martha of the news saying, “We are to be artillerymen and have got to hold an advanced position on Arlington Heights for we are the first three-year’s men so we are to be put ahead of the rest. Our new Colonel [Robert Ogden Tyler] is one of the best of men for he tried to have the men have their rights.”

Chester Chapman’s Sickness and Battle in Virginia

Chapman spent many of the following months sick, moving in and out of the hospital depending on the amount of strength he had. He worked some as a nurse and cook in the hospital before going back on regular duty with his regiment as they traveled throughout Virginia. In June of 1862, he wrote from Cold Harbor about the current doings of his regiment and the grisly conditions they faced.

“We are on a hunting expedition, we have been all over Virginia after the rebels and only got up with them once and then they almost got us in a trap before we knew that they were in sight.

There is nothing that will kill a man like this for we had to walk thirty miles one day and then run for two hours over the battlefield where we could not step in some places without stepping on a dead man and Norman Smith slept with one and kept punching him with his elbow to make him move and did not know that he was dead until morning.

We buried 25 North Carolina men in one grave. Some of them was killed so sudden that they fell just as they stood. One man lay with one hand on his gun and the other on the ramrod a trying to load it. One poor fellow had the top of his head shot off. This war business is hard when one has to walk all day to do two or three hours fighting and then have to sleep on the battle ground all night.”

Chester Chapman’s Capture and Imprisonment at Richmond

During the Seven Days Battles in 1862, Chester Chapman was taken prisoner by the Confederate army. In July 1862, Martha Chapman received a letter from another man in Chester Chapman’s regiment, Albert Sperry, stating that Chester had been captured and was currently a prisoner in Richmond, Virginia, working as nurse. Sperry expected that Chester would soon be released on parole.

On August 8, 1862, Chester Chapman was finally able to write what had become of him.

“As I have got clear of the rebels and back to my company with nothing else to do but write, I will let you know how I have been. I have been sick with the scarlet rash for about two weeks and besides all that, I have been in a Richmond prison for five weeks. I got taken at the hospital on the 27th of June by Jackson’s troops and carried to prison and fed on bread and water—and sour bread at that. But I am well at present, thank God, and hope that you are the same.”

Chester also wrote some of the deplorable conditions the sick and wounded endured.

“I wish that I could describe to you the horror of the battlefield. The one where I was was nothing to what some of them is. I went on to it a week after the fight and there lay poor men with no legs, some with broken arms, and some with all one side of their heads shot off and no one to help them for our doctors all run and the rebel doctors had as much as they could do to take care of their own men. I have seen poor men die that would have got well with a very little care for their wounds would get fly blown and the poor men would be eat up with maggots when a little cold water would have cured them.”

Chester Chapman’s Reenlistment as a Veteran and Service Until the End of the Civil War

Chester Chapman reenlisted as a veteran on November 3, 1863 and was promoted to corporal in January 1864. For much of this time there are no surviving letters between Chester and Martha. Martha came down to visit him briefly in April of 1864 and he wrote her detailed directions on how to arrive as well as a pass she could show the guards in order to be allowed on to Fort Richardson after meeting with the Provost Marshal in Washington.

Chapman’s regiment served for a time at Bermuda Hundred and in a letter from June 5, 1864, he described what it was like to be under constant shelling.

“They have been trying to see how many of us they could kill, I guess, for they have been shelling our works very hard. It makes me feel funny to have them pieces of iron fly past and burst on all sides and all a fellow can do is to trust to the Lord and let them come. When they come over, they cry furlough for about fifty time and when they burst they cry discharge.”

After the end of the war, Chester Chapman spent several long months waiting to be discharged. He once again served in the hospital and on July 14, 1865, he wrote to Martha expecting to be mustered out soon.

“I have some good news for you, and I hope that it will prove true. If it does, I shall be at home before winter for the news is that the whole of the army of the Potomac is to be mustered out except Hancock Corps. But I think that I shall stay for if I have been put on General Detail here, I shall have to stay till this hospital is broke up.”

Conclusion

The letters between Chester Chapman and his wife, Martha (Williams) Chapman paint a vivid picture of Chapman’s service throughout the Civil War. Though he spent much of his time in the hospital either suffering from illness or working as a nurse, he also faced many harrowing days on the battlefield. The full collection of letters highlights many more episodes we were unable to include here, and may be accessed through a Research Arsenal membership. We’d also like to give a special thanks to William Griffing for his tireless work in digitizing and transcribing Civil War letters at Spared & Shared.