Angry Archivist: Tracing Civil War History With a Ballpoint Pen

Working with archives and artifacts, you are bound to come across things that make you cringe or outright cry. I have been working in museums and with historic material for over 16 years now, and the things I see sometimes still shock me. No one wants an “angry archivist” so I am going to share some of the more unfortunate things I’ve encountered in this (and future) blog posts in the hopes of offering solutions so that these things can be avoided in the future.

One thing that is important to get straight right off the bat: If you are a collector of anything historic (ANY item of historical significance) you are not its owner, you are its caretaker. Bluntly, this means that this item should continue to exist long after you have kicked the proverbial bucket. Which also means that it should continue to exist in its purest form. It should not be modified in any way from its original form. Anything done to archive material or artifacts should be reversible—or in the case of conservation, be done by professionals to avoid irreversible damage. Tracing Civil War history with a ballpoint pen causes irreversible damage to documents.

The Ballpoint Pen

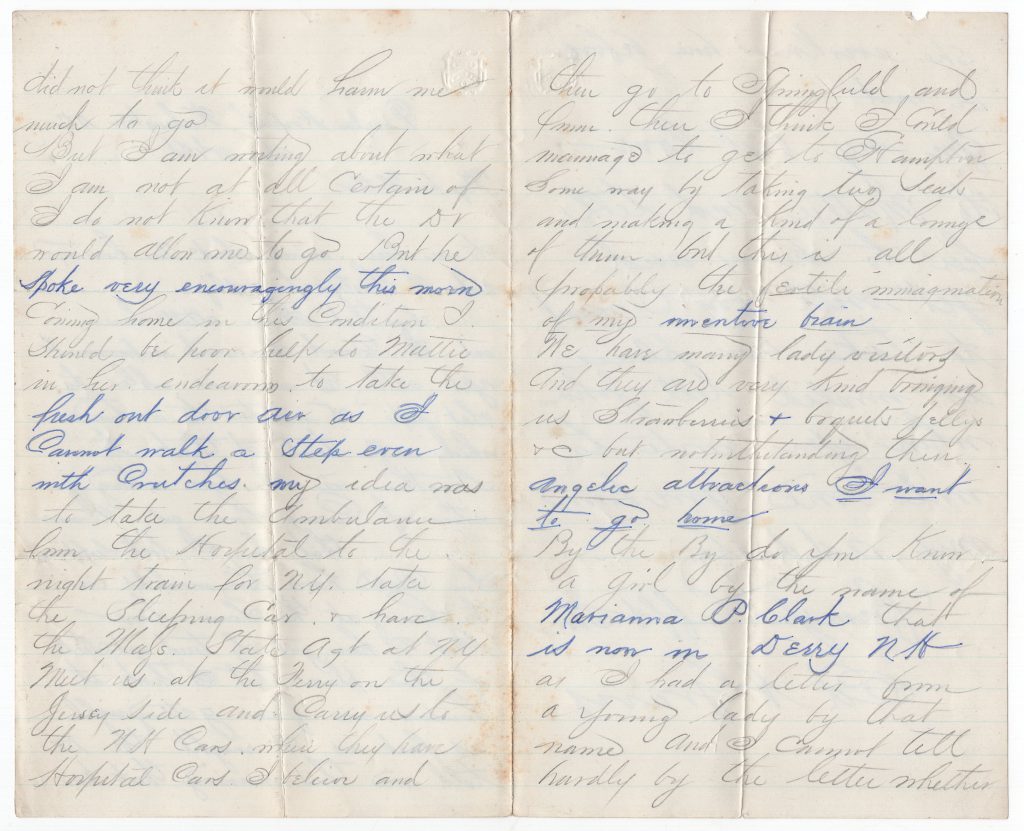

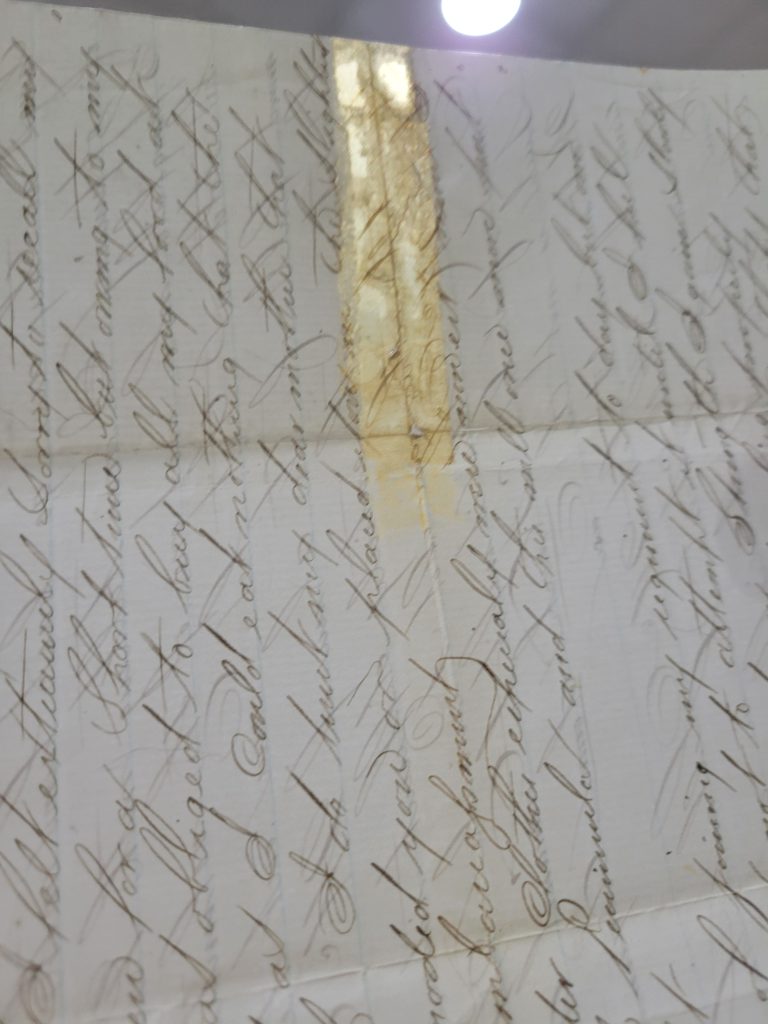

Take a look at this wonderful original Civil War letter. Look at that lovely blue ink it is written in…wait, why is it in a mixture of pencil and ink? Why does that blue ink look like ballpoint pen ink? They didn’t have those in the Civil War, did they? No, no they did not. This letter was written in pencil, but at some point in its lifetime, a former owner of the document decided it was hard to read. So, what did they do? They busted out their trusty ballpoint pen and TRACED OVER THE ORIGINAL WRITING WITH PERMANENT BLUE INK.

Folks, I cannot stress this enough, please, please do not do this. I understand that 160-year-old pencil writing can be difficult to read, but tracing over the original writing on a period document is an archival crime.

Here are some alternatives:

- Rewrite the letter onto a separate sheet of paper. Or, better yet, type it on your computer!

- Scan the letter and use a photo editing program to enhance the contrast and make the writing more readable.

- Literally anything that does not deface the original document.

The Tape

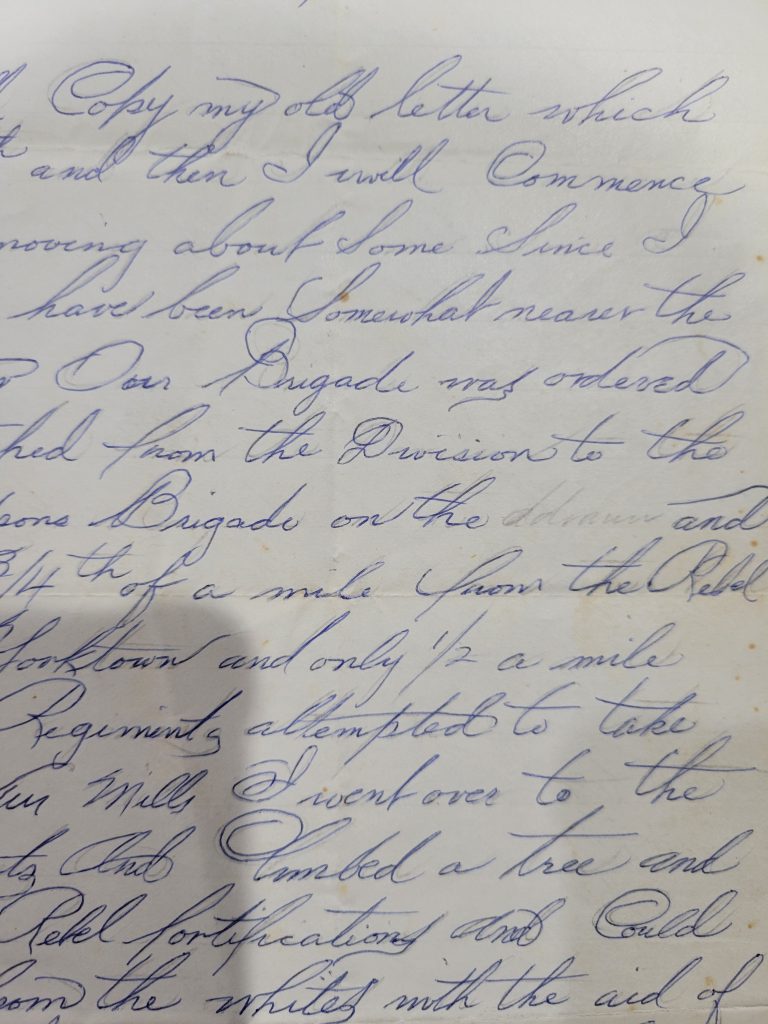

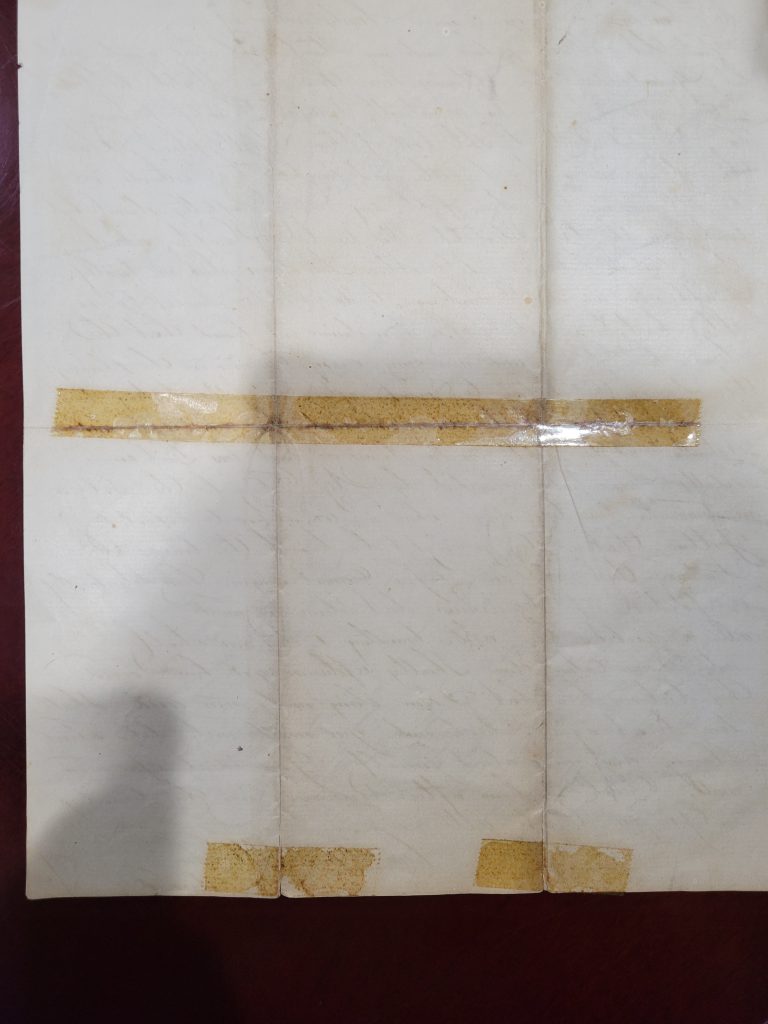

As you can imagine, documents from the Civil War are extremely fragile. Some are even falling apart. Unfortunately, for this document, not only was the pencil writing difficult to read, but it was tearing along the creases where the letter had been originally folded. But not to worry! The former owner of it knew just what to do! TAPE IT. Sigh.

Crumbly acidic yellowed tape is something I see far too often on archival documents. And I understand why people did this. The paper was old, it was falling apart, and they tried their best to keep it together. As they say, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. Unfortunately, tape is not archival—it is extremely acidic. Especially that old transparent cellophane tape from the 1960s and 1970s. Over time, it turns a beautiful shade of yellow, gets super crumbly, and begins to eat the paper. Lovely, isn’t it? And once it’s on there, much like the ballpoint pen, the damage is irreversible. In fact, if you look closely at this photo you can see where the acidic tape has actually eaten through the paper and dissolved it.

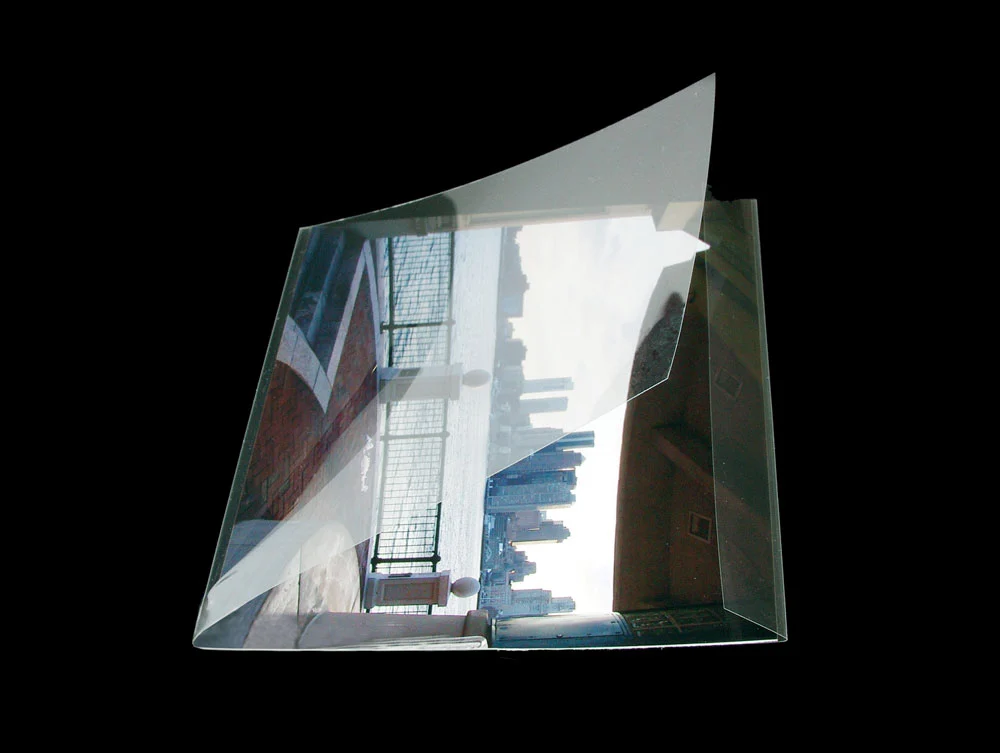

This is a quandary though. If you have historical documents like this, it’s important to preserve them. But if they are falling apart, what can you do? I’ll give you a hint, the answer is not to tape them back together. The first option I would recommend are archival sleeves. Specifically, polypropylene sleeves that are side locking. These are perfectly clear, durable, and archivally safe. This means no yellowing! Or slow acidic eating of documents! What’s better is that they are side locking. This means that you can easily open the sleeve, gently place your document inside it, and then “lock” it with the folding flap. The sleeve then safely holds your paper with a small bit of static and pressure of the top flap to ensure that it does not slide around inside. These types of sleeves come in a variety of sizes so that you can put everything from CDVs to oversized parchment certificates in them. Archival Methods is a great place to purchase some if you are interested: https://www.archivalmethods.com/product/side-loading-print-sleeves

When shopping for sleeves, I recommend the side-locking type, although there are other varieties that seal on two or three sides. I discourage using the ones that are sealed on three sides because that only allows one side to insert the document, and if it is fragile (as all Civil War era papers are) there is a much higher chance it will be damaged trying to place it in the sleeve. Because the side-locking ones are only sealed on one side, they open easily allowing you to place the document inside gently, and then fold it back over, minimizing stress on the document.

Digitize Everything

The second thing I would recommend is to digitize your documents. In museums, we always try to minimize the amount that any original document or artifact is handled. The more it is handled the more it starts to degrade. Tears on paper get bigger, edges can start to crumble, the leather on artifacts starts to deteriorate faster, etc. Once something is digitized it reduces the need to handle the original object. This is especially true with papers because they can easily be read on a high quality scan (300 dpi). Once the document is scanned, it can be stored safely in a sleeve inside an archival folder and box.

I understand that most collectors are not trained in museum and archival best practices. And I hope that sharing some of the suggestions above will help prevent more incidents like what I’ve discussed. I’ll continue to post and share helpful hints and tips on this blog and share resources of other sites that may be helpful for you in managing your collections. The most important thing to keep in mind when storing or working with your collection is: Is what you are doing permanent? If it is, do not do it. Don’t write on original documents with permanent pen, don’t cut them with scissors to better fit that neat frame you bought, don’t tape them back together, don’t hang them up in sunlight to fade, etc. You are the proud caretaker of these items, and if treated well, they will continue to last for future generations whether in private collections or museums. Once they are permanently ruined, there is no going back.

Where Can You See These Letters?

To see the letters referenced in this post visit the Research Arsenal database.

The first letter pictured can be found here: https://app.researcharsenal.com/imageSingleView/130324

An example of tape destruction can be found here: https://app.researcharsenal.com/imageSingleView/130294

The rest of the Horatio Graves letter collection can be found by searching by “Individual” and typing in “Horatio Graves” on the Research Arsenal database.